The new fast: advanced web performance best practices for 2017

Or: what Souders’ books didn’t tell you because it only happened in the last two years.

(This is a blog version of a presentation I gave at work a few weeks ago. Because I talked about a couple internal-only things, I can’t put up the video, but I hope it is worthwhile to share the slides and some notes.)

This presentation is focused on bringing you up to date on the best practices for building very fast web sites. It assumes as a pre-requisite that you already know the best practices of a few years ago, which I take to be the two Steve Souders books: High Performance Websites and Even Faster Web Sites. It focuses on the first page load rather than local cacheing strategies for speeding up subsequent loads.

To be clear, what I’m going to touch on is advanced techniques for after you already have a CDN for your static assets, minimize your JavaScript, and (most importantly of all!) minimize the bytes you send over the network.

If you haven’t read those books and followed as much of their advice as makes sense, don’t start with the things in this post.

One idea present in the books needs to be repeated loudly today: send less stuff over the wire! It is ridiculous the size of JavaScript apps, ad tracking scripts, and other random cruft that appears on the majority of websites.

But entropy is the natural progression of everything. If you’re going to start fast and stay fast, you need to have automated tools to identify changes that increase the size or time required to load your page. That way, when you add a new dependency or try out some new images, you don’t have to remember to think about performance. Externalize your care for performance into automated measurements so you can’t forget!

This is a review of the most important bits of advice in the Souders books, especially as implemented for a site like the one I work on, which is built in Rails and uses the Asset Pipeline for some of its assets. For many of us who learned performance in the era of backend frameworks like Rails, this is as much as we learned.

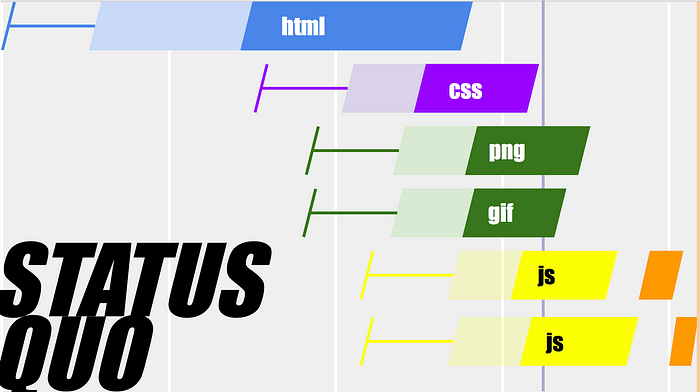

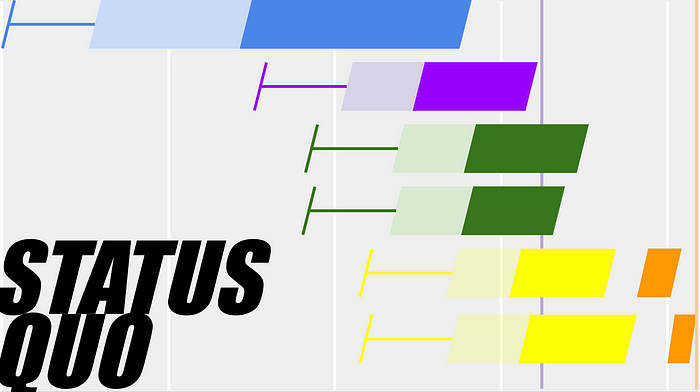

When we follow that advice, we end up with a waterfall diagram that looks something like this for a first pageview on a slow mobile connection from somewhere far away from our application server. (Throughout this post I use idealized waterfall diagrams like this without precise measurements, just to indicate the outline of what is happening.)

- The initial html request takes a while to resolve DNS & create an HTTPS connection (the blue line), then a while to send the request and wait for the first byte of the response (light blue bar), and then a while to receive all of the response (dark blue bar.)

- As the response is received, the browser discovers css, image, and javascript assets that are needed. Each of these is fetched from the CDN and requires its own new HTTPS handshake, connection, etc.

- When the css in the document head is received and processed, the browser can do a first paint (purple line).

- When the js is all received, parsed, and executed, the page’s dynamic content becomes interactive (orange line).

If we’ve been careful to minimize what we load on the page, then even on a very crummy network connection we might be able to paint at around 3 seconds and be interactive around 4 seconds.

The rest of this post is about doing better than that.

The first thing we notice about the waterfall is the wasted effort creating multiple HTTPS connections to our CDN server. The connection handshake just requires negotiations some crypto choices, so once we’ve done that once it would be nice to reuse them and save the round trips.

If our CDN supports HTTP2 multiplexing, we can save those round trips and pull in the response times of static assets fetched lower down in the page, saving up to a few hundred milliseconds in the connection creation:

Reusing the same connection may also make the requests faster, because each TCP connection starts slow and speeds up over time until it finds the available bandwidth on the connection. Using an already-warm connection thus saves time.

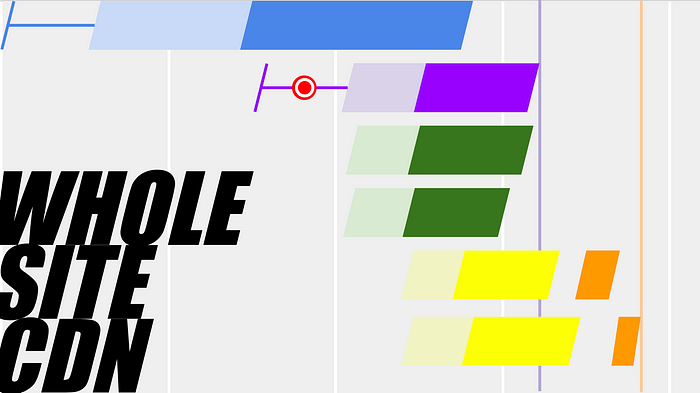

Next, we might notice that we still have two HTTPS handshakes: one to our main application server (for the html content), and another to the CDN server. Adding a CDN in front of our whole site allows even our first css request to reuse an existing connection.

Besides saving us the roundtrips for creating a new connection, adding a CDN between users and our site can drastically improve performance. Surprisingly, it can even improve performance if the CDN doesn’t do any cacheing!

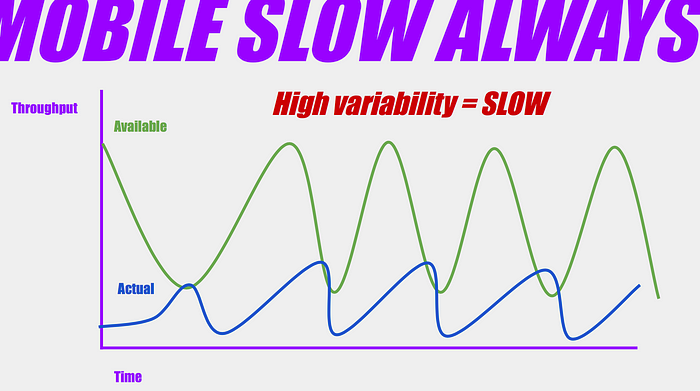

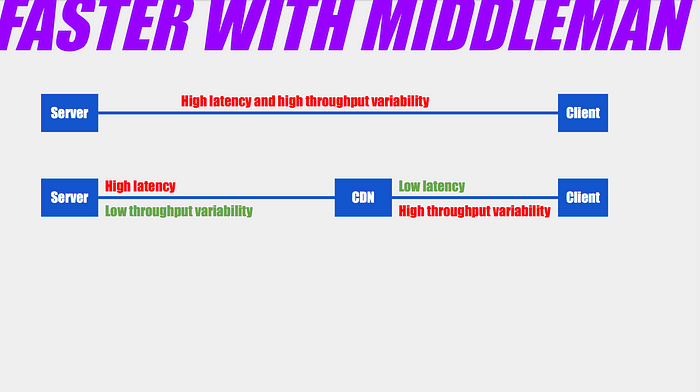

Why? Well, because of the way TCP congestion control works, two things slow down our throughput: one is the latency between the server and client, and the other is the variability of the available bandwidth. Earlier we saw that TCP slowly increases the amount of data sent until a packet is lost, then it slows down and tries again. This behavior is reasonable over stable internet connections, but produces very bad results with variable cell connections. Because of network variability, the actually-used bandwidth may be substantially less than the theoretically-available bandwidth:

The very slowest moments in the network’s available throughput determine the actually used throughput. Notice that the connection can’t take advantage of any of the times when the network connection is good, because it’s still slowly ramping up from the last time the connection was terrible.

So: high network variability makes our connection slower.

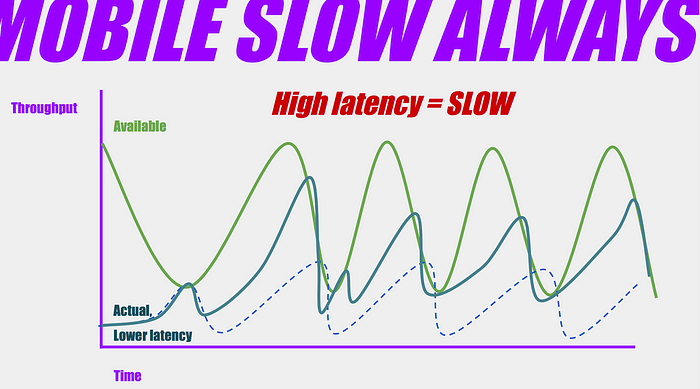

But, if the latency between the client and server is less, the connection can more quickly respond to changes in network conditions because packets are exchanged faster.

This isn’t how it works, but it’s a useful metaphor: Imagine that the cell phone is sending a message to the server saying “the network connection is good, send me lots of data right away!” If the server is 40ms away, it can send the data and have it arrive before network conditions have changed much. If the server is across an ocean, 300ms away, then by the time it receives the message and sends the data, the network conditions have changed, much of the data is lost, and the connection slows down to resend it.

So higher latency also makes our connection slower, especially in the presence of network variability.

With these two factors combined, adding a CDN between our client and server can speed things up even if it doesn’t cache but only acts as a middleman.

We’ve partitioned our two problems (latency and network volatility) into the two sides of the CDN. Between the CDN and the server, we have high latency. But the network connection is high-bandwidth and consistent, so they can still communicate quickly. Between the CDN and the client, network volatility is high, but latency is very low, so the CDN server can flush out bytes quickly when the network is good.

With the change to a CDN in front of our whole site, we’ve made some good improvements:

- The initial HTTPS connection creation is quicker, because the HTTPS handshake is done over a much smaller network hop to the CDN. (Of course, the connection between the CDN and our server should also be over HTTPS so nothing secretive is leaked.)

- Our CSS request can reuse the same HTTPS connection that’s fetching the html, so it is done sooner and we can get to first paint earlier.

Of course, once we have a CDN in front of our site, we can’t just let it serve as a middle-man. We’ll want to find (mostly-)static pages and let it cache them.

If you grew up in the era of backend frameworks like rails like I did, your idea of page cacheing might be to stick things in a redis cache or let a proxy right in front of your app server handle them. But if your application servers are in Amazon East (Virginia), having the page content cached there doesn’t do a lot of good for users in Europe or Japan. By letting the CDN cache the content, it’s closer to your customers, and therefore faster.

Of course, many pages are mostly static content, but also have an account menu in the top right or other small user-specific content. One strategy is to remove that content from the initial page request, so that it is completely cacheable, and then adding it back in via JavaScript on the client side. This isn’t a good idea for pages that are primarily about user-specific content, like an account screen. But for a home or marketing page that is static except for one little dropdown, it can save us the cost of all the round-trips needed to fetch the page content. (In this example, I’ve pegged it at about half a second!)

Now our initial document request is faster, and even our assets are getting here a lot sooner. But notice that even though the document and the assets all live on our CDN server, and even though it’s easy to tell that someone requesting our home page will need our main css file, we still don’t start loading it until the browser receives the reply and parses through it. We can do better than that!

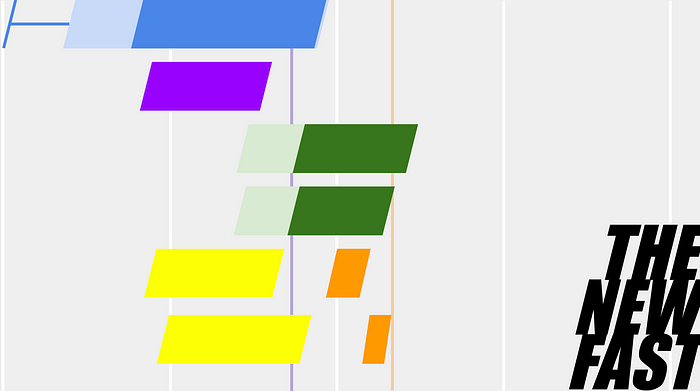

With HTTP/2 server push, we can configure our CDN server to know what static assets a page requires, and start pushing them to the client right away. This makes such a big difference, I have to reformat the title on our waterfall diagram:

Using server push, we save all the time wasted between the server starting to send the response and the browser realizing it needs to make more requests and starting to receive them. Individual assets may take a little longer to load than before because they all fight for network bandwidth, but they start so much earlier it doesn’t matter.

Notice in this example that our css now loads before the browser has even received all of the document html, so it is able to paint the top of the document right away and then progressively paint as the rest of the content is received.

Being able to paint our header, page title, and the first bit of content is a huge win for perceived performance.

Now, server push requires some discipline. In particular, while it’s very effective for a first page load, it becomes wasteful on subsequent page loads if the server is pushing assets that the browser already has cached. So once we adopt server push, we also need a way to indicate to the server that we don’t want global assets pushed to us anymore. There are various ways to do this depending on how your site is structured. You can look them up when you need to.

What we’ve accomplished

With the best practices of just a few years ago, we had a site that was pretty darn fast:

By sprinkling in the new powers of HTTP2, whole-site CDN, and server push, we’ve now got a site that is really damn fast:

That’s a big difference. For an ecommerce site, it could be a difference of several percentage points in conversion rate. You do know your site’s funnel metrics, right? Multiply it out to see what it might be worth to you.

Learn more

- Read High Performance Browser Networking, a free online book that describes the web network stack in detail, all the way down to cell hardware.

- Watch Alex Russell’s Progressive Performance talk, which covers ways to measure real-world performance and some of the problems you wouldn’t expect.

- Learn how to split bundles and remove unneeded code in Webpack, or your build tool of choice.

- Work through the Offline web applications course on Udacity to learn about using service workers and client-side cacheing techniques to make your site even faster on subsequent loads.

A final word

It is very tempting — I know, it happens to me! — to think about the steps in this blog post and all the advanced configuration and ops work that could make your site faster. Shiny new things are always fun to think about.

But you have a site that’s up now and could be faster. And there’s about a 98% chance you have a lot of work to do before you should start thinking about the stuff in this post.

But before you do any of this, please, please, first make sure that you:

- have real devices, slow Android phones, for doing measurements

- know how to use network link conditioner to simulate realistic network conditions

- set up automated performance measurements of your real site as it is today and of new builds to catch performance regressions

- split your JS and CSS so that you only load the bare minimum you need for initial render, and async load the rest

- know the weight of your dependencies and have consciously chosen to use them (evaluate using Preact instead of React, for example)

If you’re that far, then by all means, go have some fun with the shiny new things that can make your already-fast site even faster.